Here we intend to explain

influences of the frame on an object within it. Moreover, all the forces

acting upon an object within the certain field of vision - the field of

our image. While for the primary, orientational forces (being left and

right, and up and down) existence of frame isn't essential - it is sufficient

to (self explanatory in deed) have basic spatial orientation, all of the

other forces are directly caused and determined by the frame itself. Our

illustrations try to assume the simplest possible "laboratory isolated"

shape - a circle (presumably an abstract denominator of every object's

manifestation) in an empty horizontal frame, roughly proportioned by the

golden rule. The belief is that every example is applicable to any object

in any other shape or proportion of the frame. It only remains to be mentioned

that in practical cases, instead of the clean and isolated influences,

we'll find a sum of different forces, often the contradictory ones, all

around the very detail we are trying to figure out. Besides, our visual

memory is usually sufficient to install chaos even in a blank paper. That's

why these "clean" illustrations to follow need an equally innocent eye.

From there, what follows is quite simple.

up and down

The only thing necessary for this grid of forces to appear is some

kind of decision or realization about what is "up" of what we see, even

if we are looking at an action painting laid down on the floor. (It could

be argued that floor is a natural habitat for many of those, which they

lost due to traditional establishment of the wall.) This kind of work,

just like some structuralist images and many ornaments, does not contain

information about what is up and down. Therefore, the "gravitational" order

of our visual field is something inherently subjective - not necessarily

predetermined - it emerges from our relation to the seen. Our eye will

establish this order no matter how we turn the image - and it is possible

that the composition will "function" in each case - although it will for

sure function in a significantly different way.

Since the whole hierarchy is gravity based, the altitude of the object

within the image is directly connected with its potential energy. That

is why everything that is higher up looks bigger and heavier, and the first

impression of turning a quiet and settled composition upside down is as

if everything is going to fall and tumble over each other. In this relation

the characteristic of super- and inferiority is very clearly stated. Our

impressions about this order are almost of an architectural nature: we

see things leaning on the others, weighting them, being built on them,

coming out of something, still supporting some others above, etc., which

is all obviously hierarchical. Ambivalence of these attributes manifests

itself accordingly: an object on the bottom can offer an impression of

rest, peace, emptiness, and exhaustion. In the other context, it can radiate

with ambition towards all the space awaiting it above. These are literary

two opposite forces applied to the same spot. In need of example, we can

use a head of the person within a portrait. |

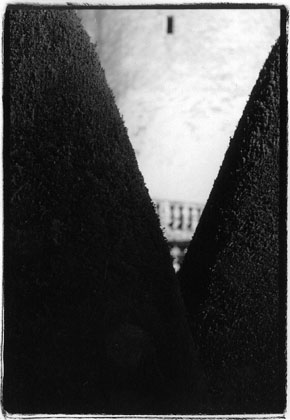

Even though the little window has the position of utmost

height and power, the claustrophobic feeling of closeness to the edge and

being squeezed by the remainder of the image turns the emotion towards

confinement, limitedness, and sorrow, despite its pride.

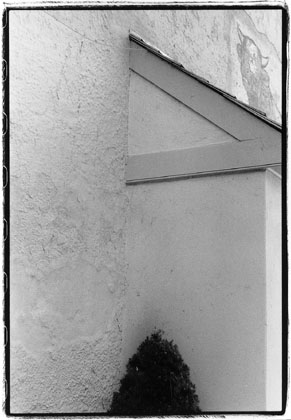

The opposite is the role of a small bush bottom center.

Having so much space above, and attracted by the relations with the higher

placed objects, it shows a climbing tendency, even though it retains the

power and weight of the earth. (On the wall above is a painting of the

bull's head.)

|