Elaborating the relations

of object with different sides of the frame is mostly a synthesis of

what was already said about up and down and left and right, with the previous

chapters about the image's edge. The extremes of up and down can, for our

symbolic purposes, unmistakably be represented by heaven and earth. Bottom

edge of the image is a stabile, solid border, suitable for support of the

heaviest weight, and the most appropriate foundation for something to sprout

up and grow out of. Top of the image, on the contrary, is an labile phenomenon

of rather spiritual matter. Left and right sides have their best description

in properties of left and right within the image: intuitive and self-oriented

versus rational and turned outwards. All this is a good testimony about

asymmetry within the frame, ignored in the past two chapters.

The above mentioned properties make the sides group in pairs: and that

is left and up, and right and down. These are, therefore,

the most opposite corners. (Of course, just to keep our awareness balanced –

whatever is valid for the contact with a particular side, certainly is

felt as an influence throughout the surface of the image.) From all this

follows the difference in impression of a line coming out of a particular

side.

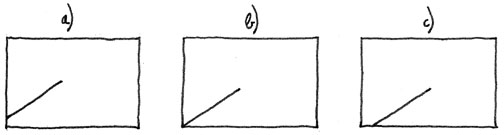

Particularly interesting is a line emerging from a corner (as a diagonal).

The converging sides suggest a feeling of perspective here, and it really seems

one can follow a diagonal into a corner without ever reaching the frame,

because it meets it at the ends of the sides, together, in a perceived infinity.

As well, just because this is the farthest point ("of the world"), there

is some mystical power, enhanced by the sharpness of the vanishing point,

"there, on the horizon". Comparing this with the line that comes out from

the side, where the cut is dominant and precise as a momentary

transition into non-dimensional, line coming out of the corner is preserved

in all its length, beginning with the optical perception itself.

Fig.'s

a),

b) and c) show drastic difference in

impression between something that is mechanically indeed minimal change

(such as the small camera movement in film and photography).

mutual influence of the objects

This is where we lose the ground under our feet of theory: the abundance of all that's

possible within image makes a clear analysis impossible, or at least vastly exceeding the scope of this text.

At least some first steps of this exploration

can be found in "Art and Visual Perception" by Rudolf Arnheim, a book that

I gladly recommend. Those helpful tools, just like the elementary visual phenomena studied and described here, can be used

as an alphabet in interpretation of more complex events such are

mutual relations of objects inside the image. |