Relations among elements of a whole,

if definition is what we are after. Experience of that "whole" seems quite

plausible, as a sum of our impressions of, in this case, an image.

It is a bit more of a job to discern and describe the "elements" and "relations".

"Every visual presence is a visual influence". This compact wisdom

of Rudolf Arnheim wakes us up to the realization of an alive,

organic mechanism, discouraging a clean-cut scientific approach.

That is why some of the best foundation for this can be found in the Gestalt

psychology, which avoids former scientific problem by explaining the perceptory phenomena's

through inner instincts of a human psyche. One of the basic premises of

Gestalt is that the whole is more than just the sum of its components.

That is how we would like to understand a composition of an image: as an conglomerate

of innumerable forces, many of which functioning subconsciously, some

which are hard to measure, and most of them impossible to experimentally isolate.

It is only if all of them are acting in some mutual agreement that we can

speak of a good composition - or, if the bunch isn't working together,

a bad one.

There is no (or at least no more) such thing as

a beautiful or ugly composition. That is generally an obsolete term in service of traditional aesthetic - a discipline aimed

towards resolving of all the conflicts already on the first formal level (in

pursuit of what was called beauty). The result was a premature death

of almost all the potential that primary visual components of the image have – composition itself rarely used to be a tool of expression. All this does not

mean that the "new" aesthetic unconditionally leaves all inner conflicts

unresolved, but rather that it values direct visual expressiveness before

the flawless polish. With some theatrical irony, we could generalize that the traditional aesthetic positions itself

towards death, and the "new" one towards life. Of course, that means missing

the point: the main difference is in the attempt of moving expressiveness

into the levels essential for media itself. Insistence on the active participation

of viewer is caused by the need for him to employ his impressions which

collect and bridge the gap between formal "imperfection" and ideal perfection.

This intent of finishing the work by the absorption and anticipation in

viewer's mind could also be the sign of a certain humanitarian renaissance which denies

the "astral" or "infinite" beauty of the art and makes it an work of a

man for another man, where both are equally important.

One of the most common attributes of a composition, which we

will later try to explain in examples, is the ambivalence of its elements.

The principles of dialectics seem to be strong here: a minute particle of the composition can often be a cause of two quite contrary effects.

Which extreme will it be, depends of course on all the other elements, but

also on the viewer position, which can easily fluctuate between the opposites

of empathy, and relation towards the image. All this isn't of much help

when trying to sort the situation out. But hey, it is actually very simple

and elementary physics: every force in nature has its counter force, equal

in strength, but opposite by direction.

|

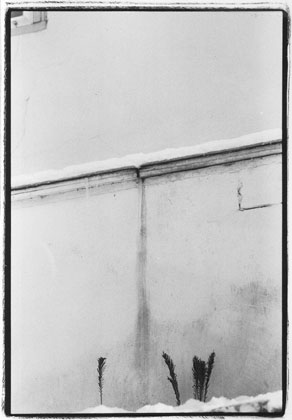

This unconventional composition tries to facilitate

its full visual potential: only the essential is present, in careful amounts.

Positions inside the frame correspond with emotional meanings of objects.

Collectively, these forces form an idea which can be, as in music, called composition.

|