It is just amazing with how much

vague generalization this term usually gets when applied to visual matter.

Rhythm became a popular term for expression of a whole load

of unarticulated feelings about the image – while at the same time, the

official definition is frugal: "(orderly) repetition of visual

elements". Now, this orderly repeat is only the simplest form, the lowest

level still going as an idea of rhythm. In music (which, in comparison,

seems so structurally advanced), this would be called "a tempo", almost

derogatively so, like a metronome beat itself. Are we dealing with an inferiority

of the eye here? Let the ear show us the way: the complexity of rhythmic

shapes only starts with repetition, and then goes into a variety that is seemingly easier to hear than see.

What is important here for the perception

of rhythm is the feeling of that mentioned tempo. It seems that

the help we need is a sort of coordinate system: this is somewhat a condition

(and an integral part) of the rhythm. Which means, if this isn't quite

a rhythm:

oo o o oo o o oo ooo o o, then

this for sure is:

oo...o.o.oo.o...o.oo.ooo...o..o.

The obvious question

is just where do we get the coordinate system? Well, where do we get the

tempo of music before it starts? No silence, and no white paper have it.

We have to wait for the music to start and bring the idea of tempo: at

the same moment reading of rhythm begins. The visual elements of the image

are the coordinates for themselves, and their own rhythm. This also concludes

that the whole idea of tempo is just an intermediate tool, a derivative

of rhythm itself – so let's by all means leave the metronome in the practice

room.

Every visual presence causes the emergence of certain visual rhythm. It is only to be expected for the simpler

rhythms to be more available – an easier read.

Beside simplicity, one more ingredient makes the rhythm obvious: its driving

character. The real elements of rhythm are not the actual shapes and

colors in image as much as the visual forces these produce: rhythm is a

direct product and a manifestation of the composition itself. Strong and obvious

rhythm is an exhibition of strong forces which, well phased, create an

active stream of energy – that is often taken as the

dominant axis of composition. |

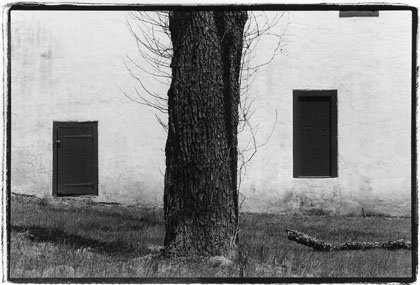

The rhythm here isn't very obvious, but its appearance

is quite interesting. A very static and strong image, anchored by the central

mass, gets the first stimulus by the right window "jumping" away from branch

on the ground. The sliver of window in the upper right amplifies that movement. Only then do we start going back, connecting

all the rhythmic elements (similar and not) into an almost ironic

mix of the two different image halves, successfully keeping the eye bouncing

around like a ping pong ball.

|